In 1895, the Lumière brothers made history by showcasing projected moving pictures to a paying audience for the first time. Subsequently, a year later, the dawn of commercial automobile manufacturing commenced in the United States. Consequently, it wasn’t long before the ingenuity of the era led to the merging of cars and cinema.

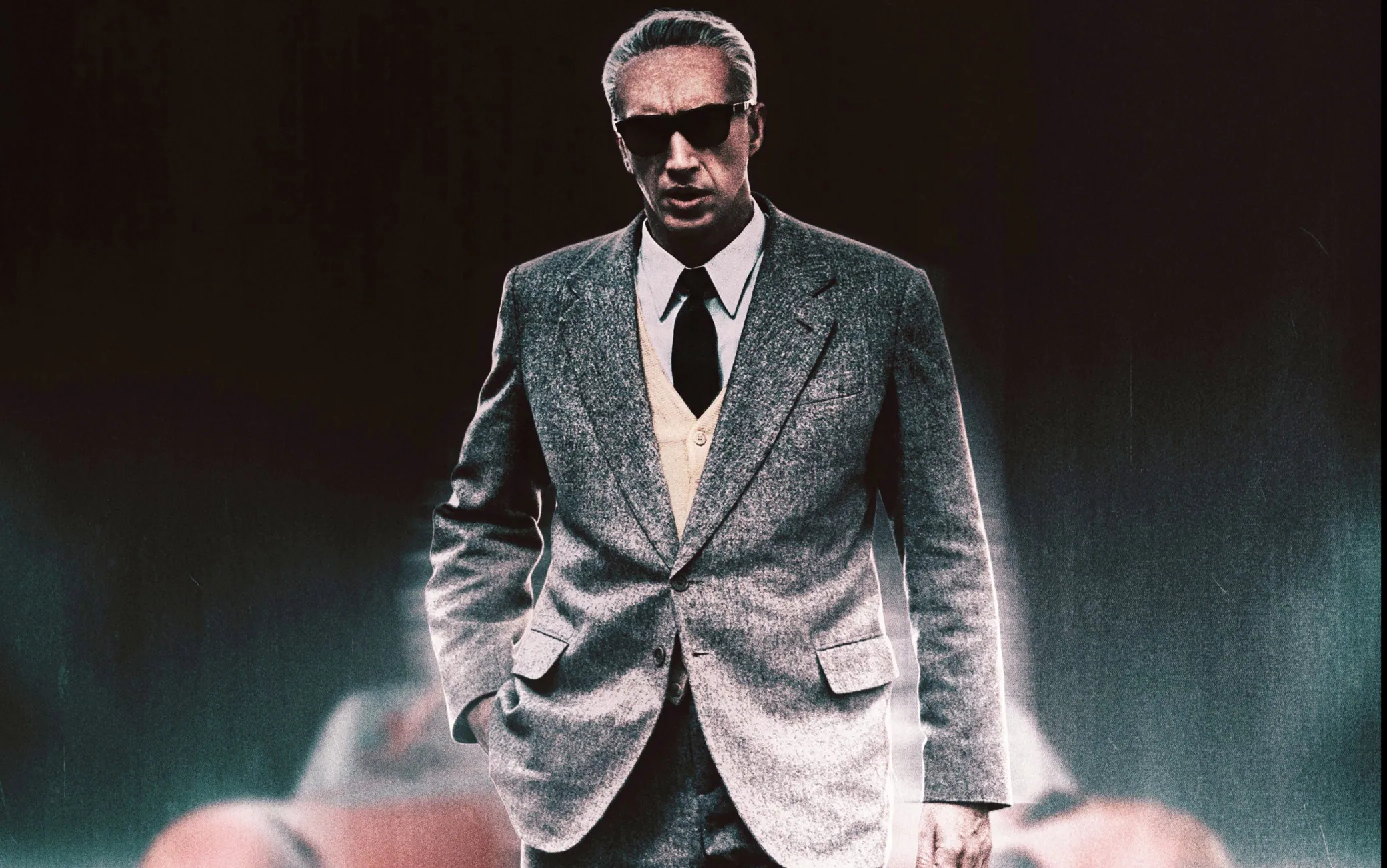

Furthermore, this synergy between movies and motors has been a constant ever since, evolving in parallel from their infancy. Significantly, Michael Mann’s latest film, Ferrari (2023), taps into this legacy, exploring the exhilarating world of car racing. The interplay of car races in films represents an intriguing convergence of technology, culture, and gender politics, stretching back to the early days of both cinema and automobile manufacturing.

Moreover, as racing found its place in the cinematic world, it initially embodied themes of freedom, power, and a rebellion against conventional norms, predominantly through male-driven stories. This narrative trajectory mirrors the broader journey of feminist theory, which challenges patriarchal systems and advocates for women’s independence and visibility in male-dominated arenas, including the film industry. Therefore, such a historical context offers a deeper perspective on the gender dynamics present in racing films, illustrating a complex and evolving landscape.

Feel the Thrill: How Mirror Neurons Put You in the Driver’s Seat of Racing Cars

Transitioning from historical context to neurological impact, there is something undeniably exhilarating in watching car races in film. The concept of mirror neurons provides a unique lens through which to examine our engagement with film. These neurons activate when we observe someone else performing an action, suggesting an empathetic bridge between ourselves, the viewers, and the characters (see Gallese and Guerra, 2020; Gallese and Sinigaglia 2011; Pisters, 2012; Zeki 1999; 2009).

Particularly in the context of racing films, this phenomenon intensifies our, making the high-speed chases and adrenaline-fueled moments more visceral. However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that while mirror neurons might enhance our emotional connection to films, their impact on our understanding of gender representations within these narratives is an area ripe for exploration.

The Need for Diverse Narratives in Racing Films

Delving into the realm of mirror neurons unveils a rich mosaic of insights, enriching our grasp of racing films and our empathetic connection with their characters. This neuroscientific perspective not only deepens our immersion in the kinetic world of racing but also shapes our understanding of the narratives and personas we encounter. Amidst the visceral thrill of car races, it’s evident that the cinematic landscape is predominantly sculpted by male-centric narratives. This observation beckons us to turn our attention to the portrayal of women in films like Ferrari.

There exists a profound and empirically validated potency in the act of immersing oneself in the exhilarating universe of car racing. Neuroscience attests to this, revealing the impactful way our brains engage with high-octane cinematic experiences. However, there remains a pressing and unfulfilled need to diversify these narratives. The goal is to evolve beyond solely male-focused tales, weaving in the rich, varied stories of minority groups. By doing so, we not only enrich the cinematic tapestry but also honor the nuanced experiences of a broader spectrum of humanity.

Plot Overview and Analysis of Female Depictions in Ferrari

In Michael Mann’s Ferrari, a compelling narrative centred around the life of Enzo Ferrari, portrayed by Adam Driver, emerges. The film’s 1957 setting is a turbulent period for Ferrari, both personally and professionally. While the plot adeptly captures Ferrari’s relentless pursuit of perfection and the looming spectre of disaster, it’s the portrayal of women that demands a critical eye. The film falls into the familiar trap of reducing its female characters to mere extensions of their male counterparts.

In Ferrari, the depiction of its female characters, particularly Penélope Cruz as Laura Ferrari and Shailene Woodley as Lina Lardi, Enzo’s mistress, warrants a critical examination for its adherence to reductive stereotypes. These portrayals are not just confined within narrow tropes; they are reflective of a broader, systemic issue in cinematic storytelling that often sidelines complex female narratives in favor of their male counterparts.

Stereotypical Portrayals in Ferrari: Laura Ferrari and Lina Lardi

Laura Ferrari, as portrayed by Penélope Cruz, is cast in the mold of the archetypical bitter and resentful wife. This character is constructed with layers of perennial dissatisfaction and emotional volatility, traits that serve to reinforce a one-dimensional view of her personality. Laura’s character is depicted as a woman whose life and emotions are inextricably tied to the successes and failures of her husband, Enzo Ferrari.

Her own aspirations, thoughts, and complexities are left unexplored, rendering her a mere satellite to the central male character’s orbit. This portrayal not only limits the character’s depth but also perpetuates a stereotype that reduces women to their relational roles, overshadowing their individual identities.

Shailene Woodley’s Lina Lardi, on the other hand, is portrayed through a different but equally limiting lens. Lina is primarily seen in domestic settings or as a sexualized figure, her character’s existence and relevance in the narrative seemingly hinging entirely on her relationship with Enzo. This representation of Lina strips her of an independent narrative arc and reduces her to an object of desire and a catalyst in the protagonist’s story. The film does not delve into her inner world, aspirations, or struggles, thus denying her the complexity and agency typically afforded to male characters.

The Need for Depth and Realism in Female Characterisations

These portrayals in Ferrari exemplify a larger trend in cinema, where female characters are often relegated to peripheral roles, constrained by clichéd portrayals. Such character treatments not only undermine the potential richness of these roles but also mirror and reinforce societal gender biases.

The film misses a crucial opportunity to explore the complexities and real-life experiences of these women. A more nuanced depiction could have offered a window into their inner worlds, their struggles, and achievements, independent of the male lead. Such rich portrayals would have not only added depth to the narrative but also aided in creating a more equitable and realistic representation of women’s roles in both historical and contemporary cinema.

Critical Reflection on Female Representation

This representation in cinema, particularly within biopics that focus on eminent men, often relegates female characters to peripheral roles, mirroring a pervasive issue in the industry. Women in these narratives are frequently diminished, serving merely as romantic interests or emblematic burdens, rather than fully realised characters.

In Ferrari, this trend is evident; women are portrayed comparably to the cars – as objects of desire, symbols of status, and even potential triggers for a man’s downfall. Such metaphorical framing does an injustice to the multifaceted nature and autonomy of women, simplifying their roles to mere narrative tools designed to either advance or obstruct the male protagonist’s arc.

The Need for a Paradigm Shift

This simplistic depiction belies the rich web of female experiences and stories that could be explored. It underscores an urgent need for a paradigm shift in cinema, where female characters are crafted with the same depth and complexity as their male counterparts. Particularly in films with significant cultural influence, there is a profound opportunity to challenge and reshape societal perceptions and norms.

Thoughtful, multi-dimensional female characters in cinema should not be an exception but a norm. They should embody a spectrum of human experiences, aspirations, and flaws, reflecting the diversity and richness of women’s lives. In doing so, films like Ferrari can transcend from being mere reflections of traditional narratives to becoming catalysts for change, inspiring new perspectives and fostering a more inclusive and equitable representation in cinema.

Such a shift would not only enrich the storytelling art form but also contribute to a broader cultural conversation about gender dynamics and representation. It encourages us to engage with more complex, nuanced narratives that mirror the realities of a diverse and multi-faceted society. The portrayal of women in cinema needs to evolve beyond the binary of love interest or symbolic burden, embracing the myriad roles that women occupy in the tapestry of human experience. This evolution in cinematic storytelling is not just a matter of artistic expression but also a step towards societal progress, challenging entrenched stereotypes and paving the way for a more inclusive and understanding world.

Concluding Thoughts: The Need for Gender Balance in Cinema

Ferrari masterfully spins a tale rich in ambition, legacy, and the daunting price of achieving greatness. However, its treatment of female characters emerges as a prominent shortfall. Despite its impressive cinematic feats, the film perpetuates an industry-wide norm, presenting women in a simplistic, one-dimensional light, thereby overshadowing their depth and agency in favor of male-dominated narratives.

For us as viewers, it’s essential to engage not just with the film’s visceral, high-octane thrills, but also to sustain a discerning awareness about how Ferrari, and films alike, portray characters across the gender spectrum. This vigilant consciousness is key to nurturing a cinematic landscape that is both inclusive and equitable, one that respects and delves into the richness of diverse narratives and character portrayals.

Mirror Neurons and Their Role in Cinematic Engagement

The intriguing concept of mirror neurons I briefly described earlier, sheds light on our interaction with films. These neurons, activated when observing others in action, forge an empathetic link between us, the audience, and the characters on screen. This neural connection deepens our immersion in the film, allowing us to vicariously experience the rush of the race or the emotional arcs of the characters. However, this immersive experience is lessened when female characters are depicted in a limited and superficial manner, a portrayal that not only narrows our viewing experience but may also echo and perpetuate societal biases.

In this way, while mirror neurons draw us into the captivating world of Ferrari, they also heighten our awareness of the film’s gender representation flaws. This empathetic bond with the characters makes us more attuned to their portrayal. Such increased sensitivity can prompt filmmakers to develop characters with greater depth and variety, mirroring a wide array of human experiences and fostering a more balanced and authentic representation of genders in cinema.

This approach in filmmaking not only enriches the narrative but also plays a pivotal role in shaping a more nuanced and egalitarian portrayal of genders on the silver screen.

Bibliography:

Galesse, V. & Guerra, M. ( 2020[2015]). The Empathic Screen: Cinema and Neuroscience (Anderson, F., Trans). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pisters, P. (2012). The Neuro-Image. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Zeki, S. (1999). Art and The Brain, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6, 76-96.

Zeki, S. (2009). Splendours and Miseries of the Brain. Love, Creativity and Quest for Human Happiness. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken.