In a nightclub filled with neon lights, young blond-haired Sascha (Victoria Carmen Sonne) looks deep into her own eyes swaying gently to the rhythm of the music. Her symmetrical face reveals a pink splash on her cheek, a mark left by her abusive boyfriend for whom she’s a trophy, nothing more than a sex doll without agency. She softly starts touching her neck, her lips, and her face, which we observe through her reflection. The grimaces appearing on her face seem unfathomable: is she smiling? Is she flirting with herself, with us, the audience? As the music continues, her dance becomes increasingly passionate as she caresses her breasts. Engulfed in her reflection, she seems ignorant about people around her.

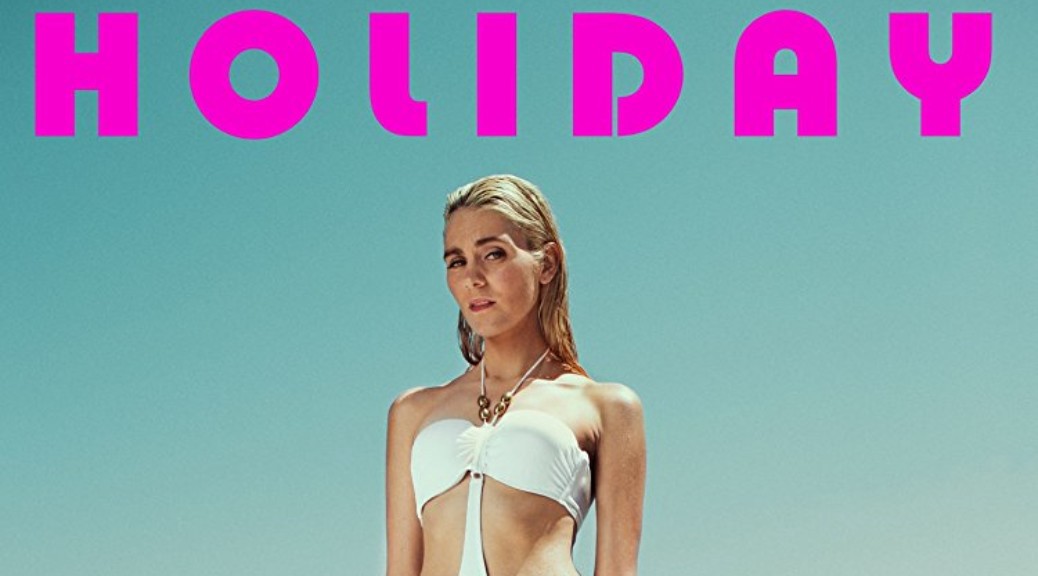

This is one of the most powerful scenes of the stark drama Holiday (2018, directed Isabella Eklöf. The film follows Sascha as she spends time in a Turkish luxury hotel resort with her middle-aged boyfriend-boss Michael (Lai Yde) and his friends. The man and his companions are involved in the drug business, which brings them money and power, but that goes hand in hand with violence and abuse- physical, emotional, and financial. Holiday does not, however, shame Sascha for being a part of this group. It also does not attempt to convince us to pity her but rather shows the strategies this young woman uses to resist being subdued by patriarchal abuse. In a world where women’s only function is to provide flesh for men in power, Sascha finds ways to re-possess her own body.

The nightclub-dance scene described at the beginning of this review is just one of the examples where Eklöf endows Sascha with her bodily agency. The person who surprisingly helps the woman, at least temporarily, to free herself from the rules of conduct imposed on her by Michael is a Dutch sailor Tomas (Thijs Römer), whom she meets in an ice cream shop. The noncommittal meetings with the man, who proudly states that his current lifestyle is his silent rebellion against the corporate jobs he worked before, give Sascha to reconsider her choices. Or that’s what Eklöf wants us to believe, only to surprise us with the unforeseeable ending. Aside from the neon nightlife, the film is starkly bright, almost clinical, with dominant whites of the luxury hotel environment. That allows for dramatic tension to grow until the film’s grand finale.

That is the power of the film, which portrays Sascha as impenetrable. She lures people around her, including us, the viewers, not unlike a siren who would lead the bewildered sailors to their death.