Over a decade ago, in the nascent stages of my journey as a photographer and filmmaker, I had my first encounter with the enigmatic works of Man Ray. This period coincided with the advent of my exploration of digital photography, marked by the acquisition of my first DSLR camera. Peering through the camera’s viewfinder, I became deeply fascinated by the transformative power of light incidence, capable of metamorphosing the mundane into the magical, transfiguring ordinary moments into sublime pieces of art.

Dadaist and Surrealist Cinematic Journeys: YouTube as a Portal to Avant-Garde Art

My quest for inspiration led me to the virtual corridors of YouTube, where I stumbled upon early films by Dadaists and Surrealists. These films, steeped in avant-garde aesthetics, induced a trance-like state, ensnaring my imagination. I found myself mesmerized by these ephemeral cinematic creations, which trod a delicate line between dreamscapes and delirium, tethering only a fragment of my consciousness to the tangible three-dimensional world.

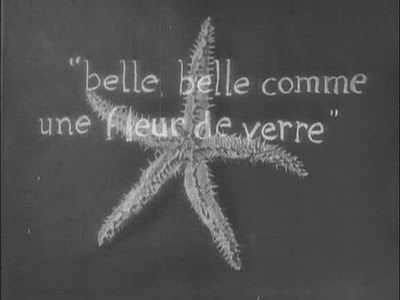

Among these artists, Man Ray’s films particularly captivated me. His works wielded a profound influence on my evolution as a photographer, filmmaker, and film scholar. I vividly recall my attempts to incorporate elements from his film L’étoile de mer (The Starfish) (1928) into my student projects, an endeavour that signified my burgeoning love for the medium and a fervent desire to challenge its conventional boundaries, much like Man Ray did with his art.

Man Ray: A Multifaceted Artistic Icon

An influential luminary of the early 20th century, Man Ray occupies a prominent position in the annals of art history, celebrated primarily for his multifaceted contributions to the avant-garde movement. His oeuvre extends far beyond the confines of any singular artistic medium, encompassing not only his trailblazing experiments with Rayographs, but also an expansive repertoire spanning painting, sculpture, and object art. Moreover, his legacy reverberates through his instrumental role in advancing the modernization of the artistic landscape.

One of Man Ray’s most remarkable and serendipitous discoveries was the innovative artistic technique known as the “Rayograph,” a term he coined to encapsulate his pioneering approach to image creation. Simultaneously referred to as “photograms” by others, this ingenious artistic method deviated from conventional photography, dispensing with the need for a camera altogether. Instead, Man Ray achieved his visual alchemy by delicately placing various objects directly onto photosensitive paper and subjecting them to the ethereal embrace of light. The ensuing outcomes were nothing short of enchanting, casting a spell of enigma and moodiness over the viewers, evoking a sense of wonderment and intrigue with each ethereal composition.

New York Dada: A Creative Nexus

In collaboration with artists such as Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) and Francis Picabia (1879-1953), Man Ray played an instrumental role in establishing a transformative artistic hub in New York City. This creative nexus, which they aptly christened the “New York Dada” movement, served as a crucible for groundbreaking artistic expression, birthing a new era of creative exploration that would reverberate throughout the international art scene.

A Cinematic Epiphany: Man Ray on the Big Screen

A pivotal aspect of my engagement with Man Ray’s films was the medium through which I experienced them – a laptop screen, via YouTube. Desperate to immerse myself fully, I would draw as close to the screen as possible, seeking a cinematic euphoria, a hypnotic escape allowing glimpses into realms beyond the constraints of space and time, delving into interplays of light and shadow.

This context set the stage for an almost transcendental experience when I had the opportunity to view Man Ray’s films on the big screen during the 14th American Film Festival in Wroclaw. The event marked the centenary of Man Ray’s first film, Return to Reason. Four of the artist’s seminal short films – Le retour à la raison (Return to Reason) (1923), Emak Bakia (1926), L’étoile de mer (The Starfish) (1928), and Les Mystères du château du Dé (The Mysteries of the Chateau of Dice) (1929) – were restored in 4K and accompanied by an original soundtrack by Jim Jarmusch and Carter Logan’s SQÜRL.

Return to Reason: Beyond Conventional Analysis

Return to Reason is an encounter, a wordless dialogue between artists, best approached as a form of meditation. Any attempt to decipher its meaning through conventional analysis renders the film elusive. This perspective might appear unorthodox, especially considering the strong ties between surrealist art and Freudian psychoanalysis, where dreams and symbols are typically dissected through the lens of psychosexual analysis. Initially, surrealism aimed to use cinema as a tool to circumvent rationality and unveil truths obscured by linguistic conventions. However, the overemphasis on psychoanalytic interpretation, particularly through the prism of the phallus, ironically ended up constraining the very unconscious realms that surrealism and psychoanalysis sought to explore.

Therefore, I propose an alternative approach to engaging with Return to Reason, one that embraces a more expansive understanding of reason, not confined to the cerebral but extending to every fiber of our being. The film invites us to interpret its meaning through our visceral, bodily reactions.

The Starfish Motif: A Sensory Guide in Man Ray’s Work

A fascinating aspect of this exploration is the motif of the starfish, recurrent in Man Ray’s work. For him, the starfish was not just an object of intrigue but an emblematic underwater entity, whose languid movements evoke primal, almost sexual energy. Drawing from Eva Hayward’s (2008) insights, starfish represent a unique form of sensory experience, being devoid of eyes yet possessing rays teeming with tactile sensitivity, responding to their environment through a kind of visual-tactile synesthesia.

While engaging with Return to Reason, we should aspire to embody the starfish, shedding our human constraints. The starfish motif liberates us from heteronormative logic, allowing us to partake in a sensual, almost amorous interaction with the film. In this queer, non-linear, and unconventional sensory landscape, we become acutely receptive to every nuance within the image – the abstract shapes, shadows, and flickering lights.

Sensory Fusion: The SQÜRL Soundtrack Experience

Adding another dimension to this experience is the music by SQÜRL. Their semi-improvised score, crafted from loops, synthesizers, and effect-laden guitars, creates a deeply experimental auditory landscape that lures us deeper into the visual narrative, culminating in a sensory fusion where music and imagery meld into an eternal oneness, challenging the boundaries of reason, finitude, and perceived truth, opening a portal to realms beyond our ordinary experience.

Psychedelia and Surrealism: Redefining Consciousness

Works Cited:

Hayward, Eva. (2008). More Lessons from a Starfish: Prefixial Flesh and Transspeciated Selves. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly. 36. 64-85. 10.1353/wsq.0.0099.